1 Background

NATS is a popular streaming system. Producers publish messages to streams, and consumers subscribe to those streams, fetching messages from them. Regular NATS streams are allowed to drop messages. However, NATS has a subsystem called JetStream, which uses the Raft consensus algorithm to replicate data among nodes. JetStream promises “at least once” delivery: messages may be duplicated, but acknowledged messages1 should not be lost.2 Moreover, JetStream streams are totally ordered logs.

JetStream is intended to “self-heal and always be available”. The documentation also states that “the formal consistency model of NATS JetStream is Linearizable”. At most one of these claims can be true: the CAP theorem tells us that Linearizable systems can not be totally available.3 In practice, they tend to be available so long as a majority of nodes are non-faulty and communicating. If, say, a single node loses network connectivity, operations must fail on that node. If three out of five nodes crash, all operations must fail.

Indeed, a later section of the JetStream docs acknowledges this fact, saying that streams with three replicas can tolerate the loss of one server, and those with five can tolerate the simultaneous loss of two.

Replicas=5 - Can tolerate simultaneous loss of two servers servicing the stream. Mitigates risk at the expense of performance.

When does NATS guarantee a message will be durable? The JetStream developer docs say that once a JetStream client’s publish request is acknowledged by the server, that message has “been successfully persisted”. The clustering configuration documentation says:

In order to ensure data consistency across complete restarts, a quorum of servers is required. A quorum is ½ cluster size + 1. This is the minimum number of nodes to ensure at least one node has the most recent data and state after a catastrophic failure. So for a cluster size of 3, you’ll need at least two JetStream enabled NATS servers available to store new messages. For a cluster size of 5, you’ll need at least 3 NATS servers, and so forth.

With these guarantees in mind, we set out to test NATS JetStream behavior under a variety of simulated faults.

2 Test Design

We designed a test suite for NATS JetStream using the Jepsen testing library, using JNATS (the official Java client) at version 2.24.0. Most of our tests ran in Debian 12 containers under LXC; some tests ran in Antithesis, using the official NATS Docker images. In all our tests we created a single JetStream stream with a target replication factor of five. Per NATS’ recommendations, our clusters generally contained three or five nodes. We tested a variety of versions, but the bulk of this work focused on NATS 2.12.1.

The test harness injected a variety of faults, including process pauses, crashes, network partitions, and packet loss, as well as single-bit errors and truncation of data files. We limited file corruption to a minority of nodes. We also simulated power failure—a crash with partial amnesia—using the LazyFS filesystem. LazyFS allows Jepsen to drop any writes which have not yet been flushed using a call to (e.g.) fsync.

Our tests did not measure Linearizability or Serializability. Instead we ran several producer processes, each bound to a single NATS client, which published globally unique values to a single JetStream stream. Each message included the process number and a sequence number within that process, so message 4-0 denoted the first publish attempted by process 4, message 4-1 denoted the second, and so on. At the end of the test we ensured all nodes were running, resolved any network partitions or other faults, subscribed to the stream, and attempted to read all acknowledged messages from the the stream. Each reader called fetch until it had observed (at least) the last acknowledged message published by each process, or timed out.

We measured JetStream’s at-least-once semantics based on the union of all published and read messages. We considered a message OK if it was attempted and read. Messages were lost if they were acknowledged as published, but never read by any process. We divided lost messages into three epochs, based on the first and last OK messages written by the same process.4 We called those lost before the first OK message the lost-prefix, those lost after all the last OK message the lost-postfix, and all others the lost-middle. This helped to distinguish between lagging readers and true data loss.

In addition to verifying each acknowledged message was delivered to at least one consumer across all nodes, we also checked the set of messages read by all consumers connected to a specific node. We called it divergence, or split-brain, when an acknowledged message was missing from some nodes but not others.

3 Results

We begin with a belated note on total data loss in version 2.10.22, then continue with four findings related to data loss and replica divergence in version 2.12.1: two with file corruption, and two with power failures.

3.1 Total Data Loss on Crash in 2.10.22 (#6888)

Before discussing version 2.12.1, we present a long-overdue finding from earlier work. In versions 2.10.20 through 2.10.22 (released 2024-10-17), we found that process crashes alone could cause the total loss of a JetStream stream and all its associated data. Subscription requests would return "No matching streams for subject", and getStreamNames() would return an empty list. These conditions would persist for hours: in this test run, we waited 10,000 seconds for the cluster to recover, but the stream never returned.

Jepsen reported this issue to NATS as #6888, but it appears that NATS had already identified several potential causes for this problem and resolved them. In #5946, a cluster-wide crash occurring shortly after a stream was created could cause the loss of the stream. A new leader would be elected with a snapshot which preceded the creation of the stream, and replicate that empty snapshot to followers, causing everyone to delete their copy of the stream. In #5700, tests running in Antithesis found that out-of-order delivery of snapshot messages could cause streams to be deleted and re-created as well. In #6061, process crashes could cause nodes to delete their local Raft state. All of these fixes were released as a part of 2.10.23, and we no longer observed the problem in that version.

3.2 Lost Writes With .blk File Corruption (#7549)

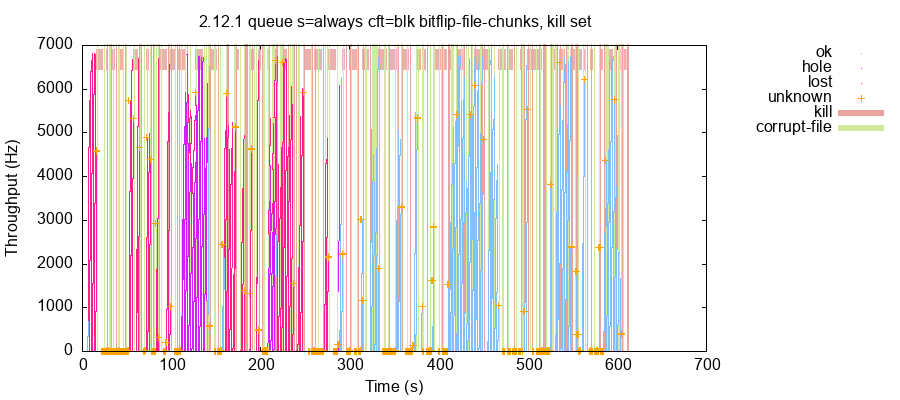

NATS has several checksum mechanisms meant to detect data corruption in on-disk files. However, we found that single-bit errors or truncation of JetStream’s .blk files could cause the cluster to lose large windows of writes. This occurred even when file corruption was limited to just one or two nodes out of five. For instance, file corruption in this test run caused NATS to lose 679,153 acknowledged writes out of 1,367,069 total, including 201,286 which were missing even though later values written by the same process were later read.

In some cases, file corruption caused the quiet loss of just a single message. In others, writes vanished in large blocks. Even worse, bitflips could cause split-brain, where different nodes returned different sets of messages. In this test, NATS acknowledged a total of 1,479,661 messages. However, single-bit errors in .blk files on nodes n1 and n3 caused nodes n1, n3, and n5 to lose up to 78% of those acknowledged messages. Node n1 lost 852,413 messages, and nodes n3 and n5 lost 1,167,167 messages, despite n5’s data files remaining intact. Messages were lost in prefix, middle, and postfix: the stream, at least on those three nodes, resembled Swiss cheese.

NATS is investigating this issue (#7549).

3.3 Total Data Loss With Snapshot File Corruption (#7556)

When we truncated or introduced single-bit errors into JetStream’s snapshot files in data/jetstream/$SYS/_js_/, we found that nodes would sometimes decide that a stream had been orphaned, and delete all its data files. This happened even when only a minority of nodes in the cluster experienced file corruption. The cluster would never recover quorum, and the stream remained unavailable for the remainder of the test.

In this test run, we introduced single-bit errors into snapshots on nodes n3 and n5. During the final recovery period, node n3 became the metadata leader for the cluster and decided to clean up jepsen-stream, which stored all the test’s messages.

[1010859] 2025/11/15 20:27:02.947432 [INF]

Self is new JetStream cluster metadata leader

[1010859] 2025/11/15 20:27:14.996174 [WRN]

Detected orphaned stream 'jepsen >

jepsen-stream', will cleanupNodes n3 and n5 then deleted all files in the stream directory. This might seem defensible—after all, some of n3’s data files were corrupted. However, n3 managed to become the leader of the cluster despite its corrupt state! In general, leader-based consensus systems must be careful to ensure that any node which becomes a leader is aware of majority committed state. Becoming a leader, then opting to delete a stream full of committed data, is particularly troubling.

Although nodes n1, n2, and n4 retained their data files, n1 struggled to apply snapshots; n4 declared that jepsen-stream had no quorum and stalled. Every attempt to subscribe to the stream threw [SUB-90007] No matching streams for subject. Jepsen filed issue #7556 for this, and the NATS team is looking into it.

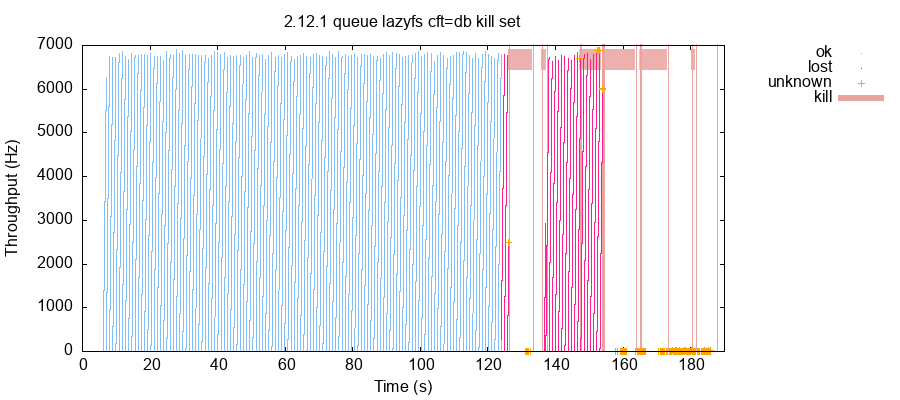

3.4 Lazy fsync by Default (#7564)

NATS JetStream promises that once a publish call has been acknowledged, it is “successfully persisted”. This is not exactly true. By default, NATS calls fsync to flush data to disk only once every two minutes, but acknowledges messages immediately. Consequently, recently acknowledged writes are generally not persisted, and could be lost to coordinated power failure, kernel crashes, etc. For instance, simulated power failures in this test run caused NATS to lose roughly thirty seconds of writes: 131,418 out of 930,005 messages.

Because the default flush interval is quite large, even killing a single node at a time is sufficient to cause data loss, so long as nodes fail within a few seconds of each other. In this run, a series of single-node failures in the first two minutes of the test caused NATS to delete the entire stream, along with all of its messages.

There are only two mentions of this behavior in the NATS documentation. The first is in the 2.10 release notes. The second, buried in the configuration docs, describes the sync_interval option:

Change the default fsync/sync interval for page cache in the filestore. By default JetStream relies on stream replication in the cluster to guarantee data is available after an OS crash. If you run JetStream without replication or with a replication of just 2 you may want to shorten the fsync/sync interval. You can force an fsync after each messsage [sic] with

always, this will slow down the throughput to a few hundred msg/s.

Consensus protocols often require that nodes sync to disk before acknowledging an operation. For example, the famous 2007 paper Paxos Made Live remarks:

Note that all writes have to be flushed to disk immediately before the system can proceed any further.

The Raft thesis on which NATS is based is clear that nodes must “flush [new log entries] to their disks” before acknowledging. Section 11.7.3 discusses the possibility of instead writing data to disk asynchronously, and concludes:

The trade-off is that data loss is possible in catastrophic events. For example, if a majority of the cluster were to restart simultaneously, the cluster would have potentially lost entries and would not be able to form a new view. Raft could be extended in similar ways to support disk-less operation, but we think the risk of availability or data loss usually outweighs the benefits.

For similar reasons, replicated systems like MongoDB, etcd, TigerBeetle, Zookeeper, Redpanda, and TiDB sync data to disk before acknowledging an operation as committed.

However, some systems do choose to fsync asynchronously. YugabyteDB’s default is to acknowledge un-fsynced writes. Liskov and Cowling’s Viewstamped Replication Revisited assumes replicas are “highly unlikely to fail at the same time”—but acknowledges that if they were to fail simultaneously, state would be lost. Apache Kafka makes a similar choice, but claims that it is not vulnerable to coordinated failure because Kafka “doesn’t store unflushed data in its own memory, but in the page cache”. This offers resilience to the Kafka process itself crashing, but not power failure.5 Jepsen remains skeptical of this approach: as Alagappan et al. argue, extensive literature on correlated failures suggests we should continue to take this risk seriously. Heat waves, grid instability, fires, lightning, tornadoes, and floods are not necessarily constrained to a single availability zone.

Jepsen suggests that NATS change the default value for fsync to always, rather than every two minutes. Alternatively, NATS documentation should prominently disclose that JetStream may lose data when nodes experience correlated power failure, or fail in rapid succession (#7564).

3.5 A Single OS Crash Can Cause Split-Brain (#7567)

In response to #7564, NATS engineers noted that most production deployments run with each node in a separate availability zone, which reduces the probability of correlated failure. This raises the question: how many power failures (or hardware faults, kernel crashes, etc.) are required to cause data loss? Perhaps surprisingly, in an asynchronous network the answer is “just one”.

To understand why, consider that a system which remains partly available when a minority of nodes are unavailable must allow states in which a committed operation is present—solely in memory—on a bare majority of nodes. For example, in a leader-follower protocol the leader of a three-node cluster may consider a write committed as soon as a single follower has responded: it has two acknowledgements, counting itself. Under normal operation there will usually be some window of committed operations in this state.6.

Now imagine that one of those two nodes loses power and restarts. Because the write was stored only in memory, rather than on disk, the acknowledged write is no longer present on that node. There now exist two out of three nodes which do not have the write. Since the system is fault-tolerant, these two nodes must be able to form a quorum and continue processing requests—creating new states of the system in which the acknowledged write never happened.

Strictly speaking, this fault requires nothing more than a single power failure (or HW fault, kernel crash, etc.) and an asynchronous network—one which is allowed to deliver messages arbitrarily late. Whether it occurs in practice depends on the specific messages exchanged by the replication system, which node fails, how long it remains offline, the order of message delivery, and so on. However, one can reliably induce data loss by killing, pausing, or partitioning away a minority of nodes before and after a simulated OS crash.

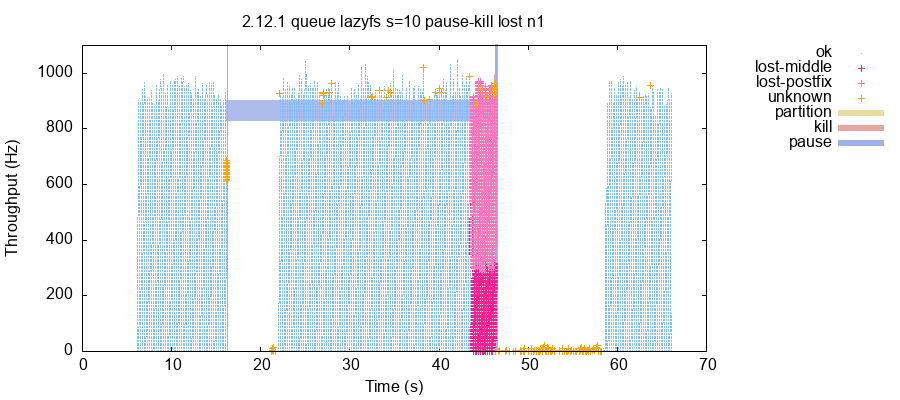

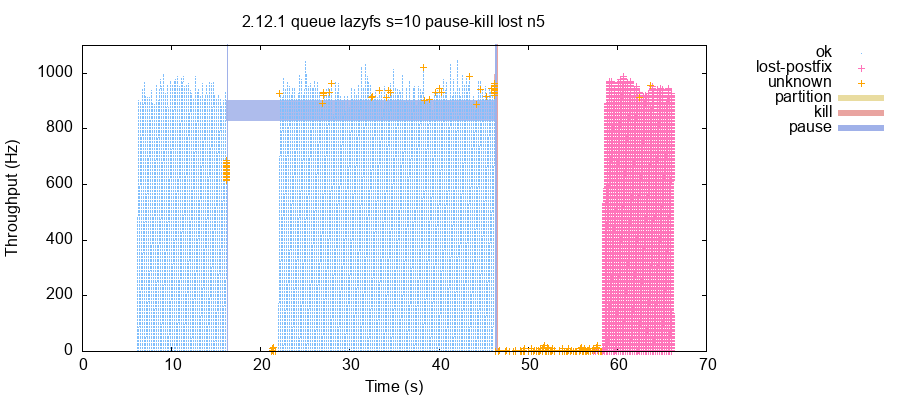

For example, process pauses and a single simulated power failure in this test run caused JetStream to lose acknowledged writes for windows roughly on par with sync_interval. Stranger still, the cluster entered a persistent split-brain which continued after all nodes were restarted and the network healed. Consider these two plots of lost writes, based on final reads performed against nodes n1 and n5 respectively:

Consumers talking to n1 failed to observe a short window of acknowledged messages written around 42 seconds into the test. Meanwhile, consumers talking to n5 would miss acknowledged messages written around 58 seconds. Both windows of write loss were on the order of our choice of sync_interval = 10s for this run. In repeated testing, we found that any node in the cluster could lose committed writes, including the node which failed, those which received writes before the failure, and those which received writes afterwards.

The fact that a single power failure can cause data loss is not new. In 2023, RedPanda wrote a detailed blog post showing that Kafka’s default lazy fsync could lead to data loss under exactly this scenario. However, it is especially concerning that this scenario led to persistent replica divergence, not just data loss! We filed #7567 for this issue, and the NATS team is investigating.

| № | Summary | Event Required | Fixed in |

|---|---|---|---|

| #6888 | Stream deleted on crash in 2.10.22 | Crashes | 2.10.23 |

| #7549 | Lost writes due to .blk file corruption |

Minority truncation or bitflip | Unresolved |

| #7556 | Stream deleted due to snapshot file corruption | Minority truncation or bitflip | Unresolved |

| #7564 | Write loss due to lazy fsync policy |

Coordinated OS crash | Documented |

| #7567 | Write loss and split-brain | Single OS crash and pause | Unresolved |

4 Discussion

In NATS 2.10.22, process crashes could cause JetStream to forget a stream ever existed (#6888). This issue was identified independently by NATS and resolved in version 2.10.23, released on 2024-12-10. We did not observe data loss with simple network partitions, process pauses, or crashes in version 2.12.1.

However, we found that in NATS 2.12.1, file corruption and simulated OS crashes could both lead to data loss and persistent split-brain. Bitflips or truncation of either .blk (#7549) or snapshot (#7556) files, even on a minority of nodes, could cause the loss of single messages, large windows of messages, or even cause some nodes to delete their stream data altogether. Messages could be missing on some nodes and present on others. NATS has multiple checksum mechanisms designed to limit the impact of file corruption; more thorough testing of these mechanisms seems warranted.

By default, NATS only flushes data to disk every two minutes, but acknowledges operations immediately. This approach can lead to the loss of committed writes when several nodes experience a power failure, kernel crash, or hardware fault concurrently—or in rapid succession (#7564). In addition, a single OS crash combined with process crashes, pauses, or network partitions can cause the loss of acknowledged messages and persistent split-brain (#7567). We recommended NATS change the default value of fsync to always, or clearly document these hazards. NATS has added new documentation to the JetStream Concepts page.

This documentation also describes several goals for JetStream, including that “[t]he system must self-heal and always be available.” This is impossible: the CAP theorem states that Linearizable systems cannot be totally available in an asynchronous network. In our three and five-node clusters JetStream generally behaved like a typical Raft implementation. Operations proceeded on a majority of connected nodes but isolated nodes were unavailable, and if a majority failed, the system as a whole became unavailable. Jepsen suggests clarifying this part of the documentation.

As always, Jepsen takes an experimental approach to safety verification: we can prove the presence of bugs, but not their absence. While we make extensive efforts to find problems, we cannot prove correctness.

4.1 LazyFS

This work demonstrates that systems which do not exhibit data loss under normal process crashes (e.g. kill -9 <PID>) may lose data or enter split-brain under simulated OS-level crashes. Our tests relied heavily on LazyFS, a project of INESC TEC at the University of Porto.7 After killing a process, we used LazyFS to simulate the effects of a power failure by dropping writes to the filesystem which had not yet been fsynced to disk.

While this work focused purely on the loss of unflushed writes, LazyFS can also simulate linear and non-linear torn writes: an anomaly where a storage device persists part, but not all, of written data thanks to (e.g.) IO cache reordering. Our 2024 paper When Amnesia Strikes discusses these faults in more detail, highlighting bugs in PostgreSQL, Redis, ZooKeeper, etcd, LevelDB, PebblesDB, and the Lightning Network.

4.2 Future Work

We designed only a simple workload for NATS which checked for lost records either across all consumers, or across all consumers bound to a single node. We did not check whether single consumers could miss messages, or the order in which they were delivered. We did not check NATS’ claims of Linearizable writes or Serializable operations in general. We also did not evaluate JetStream’s “exactly-once semantics”. All of these could prove fruitful avenues for further tests.

In some tests, we added and removed nodes from the cluster. This work generated some preliminary results. However, the NATS documentation for membership changes was incorrect and incomplete: it gave the wrong command for removing peers, and there appears to be an undocumented but mandatory health check step for newly-added nodes. As of this writing, Jepsen is unsure how to safely add or remove nodes to a NATS cluster. Consequently, we leave membership changes for future research.

Our thanks to INESC TEC and everyone on the LazyFS team, including Maria Ramos, João Azevedo, José Pereira, Tânia Esteves, Ricardo Macedo, and João Paulo. Jepsen is also grateful to Silvia Botros, Kellan Elliott-McCrea, Carla Geisser, Coda Hale, and Marc Hedlund for their expertise regarding datacenter power failures, correlated kernel panics, disk faults, and other causes of OS-level crashes. Finally, our thanks to Irene Kannyo for her editorial support. This research was performed independently by Jepsen, without compensation, and conducted in accordance with the Jepsen ethics policy.

Throughout this report we use “acknowledged message” to describe a message whose

publishrequest was acknowledged successfully by some server. NATS also offers a separate notion of acknowledgement, which indicates when a message has been processed and need not be delivered again.↩︎JetStream also promises “exactly once semantics” in some scenarios. We leave this for later research.↩︎

The CAP theorem’s definition of “availability” requires that all operations on non-faulty nodes must succeed.↩︎

This is overly conservative: in a system with Linearizable writes, we should never observe a lost message which was acknowledged prior to the invocation of the

publishcall for an OK message, regardless of process. However, early testing with NATS suggested that it might be better to test a weaker property, and come to stronger conclusions about data loss.↩︎Redpanda argues that the situation is actually worse: a single power failure, combined with network partitions or process pauses, can cause Kafka to lose committed data.↩︎

Some protocols, like Raft, consider an operation committed as soon as it is acknowledged by a majority of nodes. These systems offer lower latencies, but at any given time there are likely a few committed operations which are missing from a minority of nodes due to normal network latency. Other systems, like Kafka, require acknowledgement from all “online” nodes before considering an operation committed. These systems offer worse latency in healthy clusters (since they must wait for the slowest node) but in exchange, committed operations can only be missing from some node when the fault detector decides that node is no longer online (e.g. due to elevated latency).↩︎

Jepsen contributed some funds, testing, and integration assistance to LazyFS, but most credit belongs to the LazyFS team.↩︎